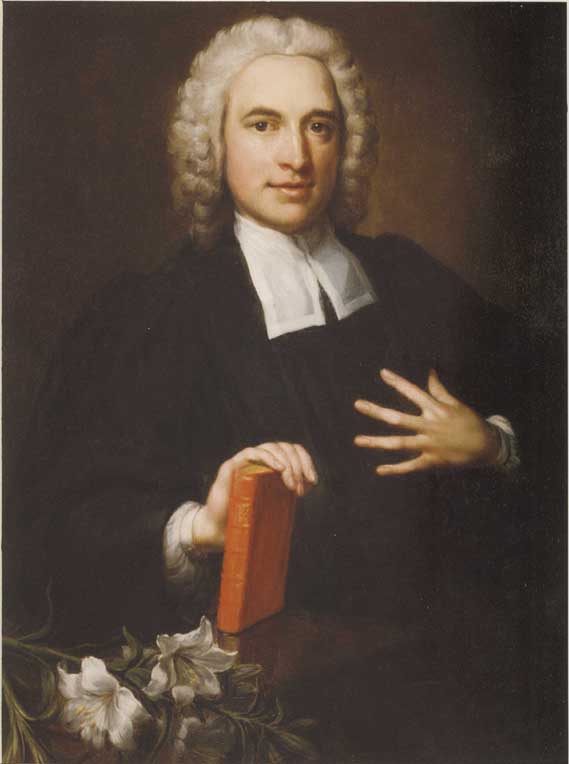

Cleric-Theologian-Hymnist

Childhood and Education

Charles Wesley was born on 18 December 1707 in Epworth. He was two months premature. His mother, Susanna, recorded that she wrapped him in wool until he was two months old and that he did not cry until the time at which he should have been born.

In His Mother’s Classroom

Like his elder siblings, Charles’s education began at home. He started his school lessons at age five, taught by his mother alongside his siblings in the rectory kitchen. Charles was a quick learner, being able to recite the alphabet and read the first verse of Genesis by the end of his first day of school.

Susanna, keen to spend one-on-one time with each of her children, spent time with Charles on Saturdays. During this time, as she did with his siblings, she would have spoken to him about his education and religion.

Westminster School

Like his brothers, Charles was sent to boarding school. Their father, Samuel, was an ambitious man and provided his sons with high quality educations. In April 1716, at the age of nine, Charles was sent to Westminster School, London. This was the same school his eldest brother, Sammy, had attended and become a teacher at following his graduation from Oxford. Due to their father’s debts, Sammy paid a substantial part of Charles’s school fees.

The eldest Wesley son also acted as mentor to the youngest. G.M. Best, a biographer of the Wesleys, cites Sammy as a key influence on Charles developing a strong social conscience and loyalty to the Church of England. This social conscience was evident during his school years, when he strongly upheld his beliefs in what was right and refused to join in the bad behaviour of others. This strength in upholding his beliefs and questioning what he did not agree with was a trait shared with his mother.

Charles excelled at school, winning a number of awards and becoming Head Boy.

Christ Church, Oxford

In 1726 Charles began studying at Christ Church, Oxford. During his first year he was not the most devoted student. His brother, John, accused him of neglecting not just his studies, but also his Christian duty. However, Charles settled into his studies and his time at Oxford proved a key stage in his Christian development.

The Holy Club

Heeding his brother’s advice to focus on his Christian duty, in January 1729 Charles and friends Robert Kirkham and William Morgan formed a religious society. The group would meet several evenings a week to pray and study the Bible. John, quickly joining the group, encouraged a constant questioning of faith.

The organised, methodical approach the group had to religion quickly attracted the ridicule of other students. ‘The Holy Club’ was a title given to the group by other students as an attempt at mockery. Another nickname they were given was ‘Methodists’, due to their methodical approach to religion. However, refusing to be mocked, the group adopted the name. Despite ridicule, the group grew in popularity and spread to other Oxford colleges. This mixture of derision and support that the group received would be echoed later, when, during outdoor preaching, the Wesleys and other Methodist preachers were either heralded, or driven from town.

The Holy Club displayed the grassroots of Methodism in other ways. They worked with the sick and elderly of Oxford, visited the city’s gaols to minister to the inmates and provided education for the poor. Such social welfare issues were key in the development of Methodism by John and Charles over the decades that followed.

Conversion Experience

Like his brother, John, Charles questioned the strength of his Christian devotion and was plagued with doubts. The 1730s proved a pivotal decade for Charles. Following the death of his father in 1735 he accompanied John to Savannah, Georgia. After an underwhelming and unsuccessful visit he returned to England in December 1736, his health extremely poor.

Two years later, in 1738, Charles’s physical health was still weak and his doubts had not abated. He had been intrigued by Moravian theology since witnessing the strong faith of a group of Moravians on their voyage to Georgia. John told his brother that their doubts and weak Christianity were because they had not had a ‘Road to Damascus moment’, which the Moravians believed important.

On 20 May 1738, Charles met with John Bray, a member of a religious society that met in Fetter Lane, London. Bray read the story of the paralysed man from the Gospel of Matthew. Hearing this passage Charles believed God would heal him, both physically and spiritually.

The next day, 21 May, Charles described feeling a strange palpitation of his heart and believed God had truly forgiven and saved him.

The spirit of God…chased away the darkness of my unbelief.

Charles Wesley

Methodism

Itinerancy

Two months after his conversion experience Charles began preaching. At first he used sermons written by John, but he quickly grew in confidence, devising his own sermons and even preaching without preparation. However, Charles did not take to open-air preaching as keenly as his brother.

Early Methodism was beset with criticisms, a main one being that open-air preaching was conducted by dissenters and the Church of England opposed it. Charles, having developed a strong loyalty to the Church of England through his parents and brother, Sammy, did not want to further offend the Church.

Other Methodists would not let Charles shy away from field-preaching. On 24 June 1739, George Whitefield, who had persuaded John Wesley to conduct field-preaching, ordered Charles to preach at Moorfields, London. The crowd was nearly ten thousand strong. Charles, for a time at least, found his doubts about field-preaching lifted.

God shone upon my path, and I knew this was his will concerning me.

Charles Wesley

That August the two Wesley brothers agreed that Charles would become the leading preacher in Bristol and John would take over the leadership of the Methodist movement in London.

Bristol Society

Taking over the Bristol Society in August 1739, Charles settled in the New Room. Continuing the interest in social welfare issues that had been developing since his schooldays, he encouraged the Bristol societies to join him in such work. They helped the poor, sick and imprisoned, and Charles gave comfort to the dying.

Disagreements with John and Loyalty to the Church of England

Both Wesley brothers stated their commitment to ensuring the Methodist movement remained part of the Church of England. John, however, was more easily persuaded to make changes that were controversial in the eyes of the established Church. Whereas Charles was keen to avoid offence.

By 1751 John was developing the Methodist movement in a way that made it appear like a new church attempting to breakaway. He increased the number of lay preachers and wanted all Methodist societies to view The Foundery (his London base) as the ‘mother church’. Charles was furious and in 1752 persuaded John to publish a statement declaring that Methodism would remain part of the Church of England.

Despite these early fractures in the brothers’ relationship, Charles continued work for the Methodist movement. He and his family had moved to London in 1771. Following the completion of City Road Chapel as the new London base for Methodism in 1778, Charles became its principal minister.

However, by the 1780s the rift between Methodism and the established Church had increased, causing further difficulties between the brothers. When a campaign began among some Methodists to split from the Church of England, John Wesley did not act either for or against. Instead, at the 1780 annual Methodist conference, the campaign was silenced and the declaration made that anyone who split from the Church would no longer be a Methodist. G.M. Best speculates that Charles and his supporters were behind this conference decision.

John further angered his brother and other Church of England loyalists in 1784 by ordaining Thomas Coke as a ‘General Superintendent’, in order to establish a Methodist Connexion in America. Charles believed John giving himself such authority was a separation from the established Church.

Marriage and Family

Sally Gwynne

Charles, unlike the majority of his siblings, had a happy marriage. He first met Sarah (Sally) Gwynne in 1747 when he was en-route to Ireland and stopped in the village of Garth, South Wales. Sally was intelligent and, although Charles was twice her age, it seems there was a meeting of two minds. However, obstacles to their union were not avoided.

John Wesley, who had espoused celibacy, believed Charles would become distracted from his work for Methodism. Sally was not perturbed by John’s opposition and travelled to Bristol and London to witness Charles’s work. John eventually came to see the union as a positive one. It was John that organised an annual income for Charles from the sale of Methodist publications, so he would be able to support his wife and future family.

On 8 April 1749 Charles and Sally were married by John at Llanlleonfel Church, the Gwynne family chapel. Four months later, the couple moved to Bristol – the street they lived on was later renamed Charles Street.

Children

They had eight children, but unfortunately only three survived into adulthood – Charles (Charley), Samuel (Sammy) and Sally. Descriptions of Charles as a father often show him as caring and keen to support his children’s education and talents. No doubt inspired by his own upbringing under his mother, Susanna, he provided his daughter with a strong education. When he realised his sons had great musical talent he sought the best opportunities to nurture this. In 1771, he moved his family to London in the hope of finding his sons greater opportunities of success with their music.

The Hymns of Charles Wesley

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of Charles Wesley are his hymns. He wrote over six-thousand, often composing them as he travelled on horseback and committing them to ink and paper once he reached his destination. He only wrote the lyrics, adding them to folk and classical pieces of the day, before John Frederick Lampe began composing tunes for him.

Love Divine, All Loves Excelling

And Can it be That I Should Gain?

Hark! The Herald Angels Sing

The Death of Charles

Charles Wesley passed away on 29 March 1788, aged eighty. He was buried in St Marylebone Churchyard, London. Ever loyal to the Church of England he refused to be buried in a dissenters graveyard.

He had seen the importance of a religious revival for supporting the social welfare work he keenly participated in. However, he did not want Methodism to become a separate entity to the Church of England.

Recommended Books about Charles Wesley

The following books are available in the Old Rectory shop and were used as references in the writing of this web-page:

- G.M. Best, Charles Wesley (Bristol: The New Room, 2015)

- G.M. Best, Charles Wesley: A Biography (Peterborough: Epworth, 2006)